Euroclear Expresses Concern Over Using Frozen Russian Assets for Ukraine's Benefit, Citing Financial Stability Risks

In a recent development that has caught the attention of financial markets and international policymakers, Euroclear, the prominent international depository, has voiced its apprehensions regarding the proposal to utilize frozen Russian assets to issue debt obligations for Ukraine. This proposal, currently under discussion by the G7 nations, aims to leverage the substantial frozen assets of the Russian Federation as collateral for generating financial support for Ukraine amidst ongoing conflicts. However, Euroclear's stance highlights potential threats to European financial stability and raises questions about the legal and ethical implications of such measures.

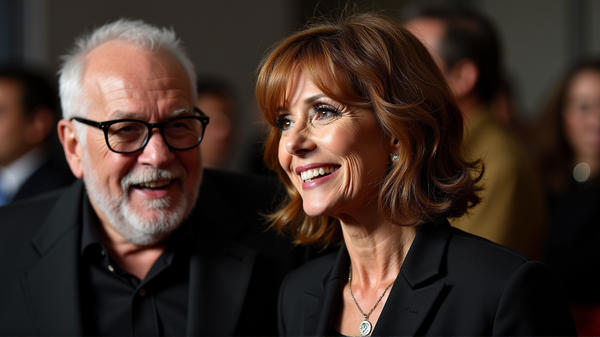

Lieve Mostrey, Euroclear's Chief Executive Officer, in an interview with the Financial Times, elaborated on the depository's concerns. Mostrey pointed out that the G7's plan could closely resemble an "indirect seizure" of assets, positioning the company at the risk of facing legal challenges. This comment sheds light on the complexity of international finance laws and the precarious position financial institutions find themselves in when geopolitics come into play.

Furthermore, Mostrey critiqued a compromise proposition put forward by Belgium, designed to navigate between the aggressive push from the USA for asset seizure and the more reluctant approach by European counterparts. The Belgian compromise would involve using the assets as collateral to secure debt, compelling Russia to later repay it, or risk asset confiscation. Mostrey likened this to an "indirect arrest or obligations for a future arrest," emphasizing the potential market impacts akin to a direct asset seizure.

Euroclear's involvement is significant due to its custody of approximately €191 billion belonging to the Russian central bank. This represents a large portion of the €260 billion of sovereign assets frozen abroad following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The handling of these assets is fraught with legal, ethical, and financial implications, especially considering the dire need for resources in Ukraine.

Mostrey expressed skepticism about the Russian central bank's acceptance of asset seizure, highlighting the ongoing obligations Euroclear has towards it. This statement underscores the delicate balance financial institutions must maintain between complying with international sanctions and fulfilling contractual obligations to their clients.

Despite these concerns, Mostrey showed a more favorable disposition towards separate EU plans to use the revenues generated from these assets to aid Ukraine. She considers this approach less risky since Euroclear does not pay interest to clients, and the revenues "legally belong to Euroclear." This perspective suggests a potential pathway that could mitigate some of the financial stability risks Euroclear identifies with the direct use of frozen assets as collateral.

In closing, it is worth noting that Euroclear reported receiving about €3 billion in interest income from the frozen Russian assets. This figure highlights the significant financial stakes involved and the complex interplay between legal frameworks, financial stability, and the moral imperative to support Ukraine in its time of need.

Euroclear's stance is a reminder of the intricate challenges faced by international financial institutions in navigating geopolitical conflicts. As discussions continue among the G7 and European Union regarding the best approach to support Ukraine while ensuring financial stability, the perspectives of key stakeholders like Euroclear will be crucial in shaping the eventual outcomes.